“The

Bluest Eye”, by Toni Morrison.

Notes

on Part One: “Autumn”.

n

Response to the style/structure of the opening

chapters preceding “Autumn”.

“Autumn”

p.16: Mr. Henry arrives/Pecola arrives

p.20—doll description

p.27—Pecola’s menstruation

Characters

Pecola—“She came with nothing.” –p.18; p.43: “She struggled

with an overwhelming desire that one would kill the other and a profound wish

that she herself would die.”/ p. 45: “Please God, make me disappear….Only her

tight, tight eyes were left.”/ p.46: “It occurred to Pecola that if …her eyes

were beautiful... she herself would be different.”

Pecola’s father

Protagonist—9 yrs

Protagonist’s sister Frieda—10 yrs.

Mrs. MacTeer. Protagonist’s mother—p.24 “My mother’s fussing

soliloquies always irritated and

depressed us”; “She would burst into song and sing all day.” Fusses about the

here quarts of milk. P.26: Morrison

develops her vernacular tone of voice as she complains about her poverty. She

beats the girls upon Rosemary’s informing her that they are “playing nasty”

without even asking for an explanation. Contradictory though as she then holds

the girls’ heads to her stomach in a very tender way.

Rosemary Villanuci—Next-door ‘friend’ offers “to pull her

pants down” to stop beating from sisters.

Mr. Henry Washington—“our roomer”. Older, not young. Not

married. A “steady worker”. Humorous and charming when he meets the girls “You

must be Greta Garbot..”

Miss Della Jones—Mr. Henry’s previous crazed landlady

Old Slack Bettie—Madame

Peggy—One of OSB’s girls who ran off with Della Jones’ husband.

Cholly ‘Old Dog’ Breedlove—having put his family outdoors

(worst thing you can do—p.17) “an old dog, a snake, a ratty nigger”. Does not come to visit his daughter even

after being released from jail. Whisky drinker.

Mrs. Breedlove—staying with the woman she was working for.

Has one twisted foot.

Sammy Breedlove—with another family. p.43: “He was known, by

the time he was fourteen, to have run away from home no less than twenty-seven

times.”; p.44: “Sammy screamed, “Kill him! Kill him!”/

Three Whores: China, Poland and Miss Marie. They live above

Pecola and are only ones to offer her kindness. Three merry gargoyles. Their conversations are

amusing and provide some light relief…but the humor is dark as they remember

failed relationships and missed opportunities. They are economically empowered

to some degree though. They use men for their own gain. “These women hated men,

all men,, without exception.”

Relationships between

characters:

Protagonist hates Pecola at first. “Unsullied hatred.” –p.19

Style

Ironic. Deadpan.

Shocks reader with unexpected undercurrent of violence; “Our house is

old, cold and green”—basic vocabulary of narrator reflects her lack of

education and the barren nature of her environment; “Adults do not talk to

us—they give us directions.” –alienating view of ‘parents’; use of dialogue (p.13) that develops ‘gossipy’

nature of the environment; humor is also conveyed in dialogue; crucially the

girls only overhear descriptions of these people; there is little direct

communication between parent/child and when there is it is admonishment for

being sick and therefore unable to work; musical descriptions of

conversation—p.15; sensory description of smell of Mr. Henry—sensual; ominous

sensuality—the girls put their hands all over Mr. Henry as they search for the

magically disappeared penny;

Semantics: “There was a difference between put out and being

outdoors.” –p.17

Animalistic imagery: ““an old dog, a snake, a ratty

nigger”—p.19

Setting:

1939 Buick; Zick’s Coal Company; food shortages; pick up

pieces of coal from industrial railway line; poverty; school; “Our house is

old, cold and green.”—Para. 2 of p.10.

Next to a coal works; $2.50/week –a “big help” to the family

p. 33: “There is an abandoned store on the southeast corner

of Broadway andThirty-fifth Street in Lorain, Ohio.” –used to be a pizza

parlor, a bakers and a house for gypsies. There was a fluid population in this

part of the city. BREEDLOVES’ HOUSE

and they lived there anonymously.

p.35: “There is nothing more to say about the furnishings…

They had all been… manufactured… in various stages of thoughtlessness, greed and

indifference.”

p.25: “Roosevelt and the CCC camps.”

Pervasive cold.

Narrative Voice: “But

was it really like that? As painful as I remember? Only mildly.”—this is a narrative

vice that reflects on the past.

p.12—“Our roomer. Our roomer.” –repetition reflects the

confusion of the girls at the time who did not understand who this man coming

to live with them was.

p.15-“…their conversation is like a gently wicked dance.”

p.22—says she does not want to possess the baby

doll—contradicts herself.

p.23: Sadistic—transferred violence. “If I pinched them,

their eyes—unlike the crazed glint of the baby doll’s eyes—would fold in pain.”

p.48: Third-person-limited voice of Pecola delivered in a

stream-of-consciousness style allows us to experience the world from her

perspective

Themes:

n

Economic disadvantage—had they not been a poor

family, they would not need to accept a roomer and then…. ; p.38: “(The

Breedlove’s) lived there because they were black and stayed there because they

believed they were ugly.” They were convinced of their own ugliness (probably

forced upon them by Cholly’s abusive behavior).

n

Ownership: p.48/49: “She owned the crack that

made her stumble. She owned the clumps of dandelions , whose white heads, last

fall, she had blown away… and owning them made her part of the world, and the

world a part of her. The things that

Pecola ‘owns’ are imaginary but gives her something real for her to hold on to.

n

Escapism: p.46/start of each chapter. The (moronic)

repetitive chanting of the idealized white world. “Pretty eyes. Pretty blue eyes. Big blue pretty eyes.”

n

Relationship between the State and the

individual/family: p.16 “The county had placed her in our house...”; “She just

came with a white woman and then sat down.” –p.18;

n

American Dream (dissolved?); p.17 “(poverty)

breeds a hunger for property, for ownership”;

p.39: “On Saturday morning, one by one, the family slipped out of their

dreams of affluence and misery into the

anaonymous misery of their storefront.”

n

Disillusionment of authority figures: p. 21—“Tears

threatened to erase the aloofness of their authority.”

n

Racial inferiority: p.22: “What made people look

at them and say, ‘Awwww’, but not for me?”

n

Men’s mistreatment of women. Violent domestic relationships. P.40: Cholly

had come home too drunk to fight. (later that morning)…the fight would lack

spontaneity; it would b calculated, uninspired and deadly.”

n

Ironic/sardonic view of religion. P.42.

Structure: Intriguing

statements which refer to later events creating dramatic tension: p. 16: “We

loved him. Even after what came later…”

Important Quotations:

p. 17 “Outdoors, we knew, was the real terror of life. The

threat of being outdoors surfaced frequently in those days.”

“…a minority in both class and caste.”

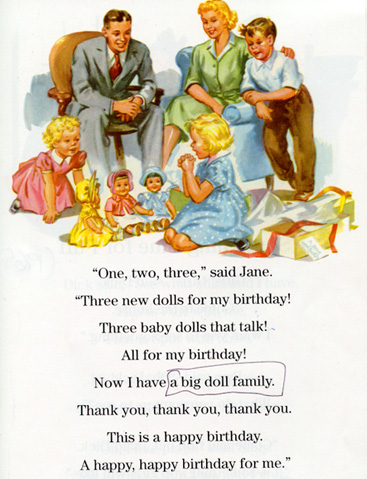

p.19 “It had begun with Christmas and the gift of dolls.”

p.22: “I destroyed white baby dolls.”

p.41: “You say one more word and I’ll split you open.”

p.42: “The flashlight did not move. For some reason, Cholly

had not hated the white men; he hated, despised, the girl.”

p.42: “She needed Cholly’s sins desperately. The lower he

sank, the wilder and more irresponsible he became, the more splendid she and

her task became. In the name of Jesus.”

p.43: “Don’t, Mrs. Breedlove. Don’t”

p.46: “Every night, without fail she prayed for blue eyes.”

p.48: “How can a fifty-two-year-old white immigrant

store-keeper…see a little black

girl?”/ “She looks up at him and sees the vacuum where curiosity ought to

lodge. And something more. The total absence of human recognition—the glazed

separatedness.”

Symbols:

p.35 Pervasive crapulence of the sofa that dominates the

house.

p. 36: “The fire seemed to live, go down, or die, according

to its own schemata. In the morning however, it always seemed fit to die.”

Motifs:

Flowers:

Marigolds: p.5. “We thought, at the time, that it was

because Pecola was having her father’s baby that the marigolds did not grow.”/Dandelions:

p.49. “Dandelions. A dart of affection leaps out from her to them. But they do not look at her and do not send

love back.”

Sweets:

p.50: “To eat the candy is somehow to eat the eyes, eat Mary

Jane. Love Mary Jane. Be Mary Jane.”

Colors:

Black: p.49. “So, the distaste must be for her, her

blackness… But her blackness is static and dread.”

Music: Pecola’s mother’s songs. The blues songs of Poland.

Activities:

Very close study of opening chapters that leads to close

literary analysis and establishing key aspects of the text: setting; style;

characters; themes; symbols/motifs etc.

p.13: “That old nigger…” –refer to “The Meaning of Nigger”

essay

p.15-“…their conversation is like a gently wicked

dance.”—listen to black people talking (do we have a video?)

p.20-22: Analyze baby doll passage. –have someone bring in a

baby doll.

p.35: Mapping the Breedlove’s House.

Explain who Ginger Rogers and Greta Garbot are.